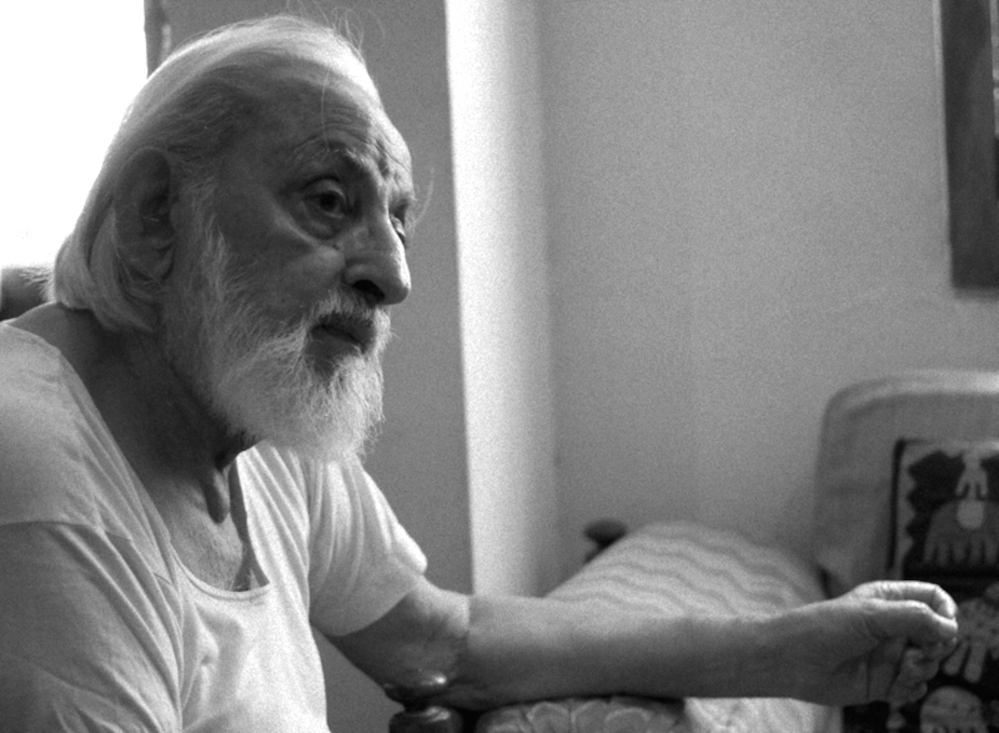

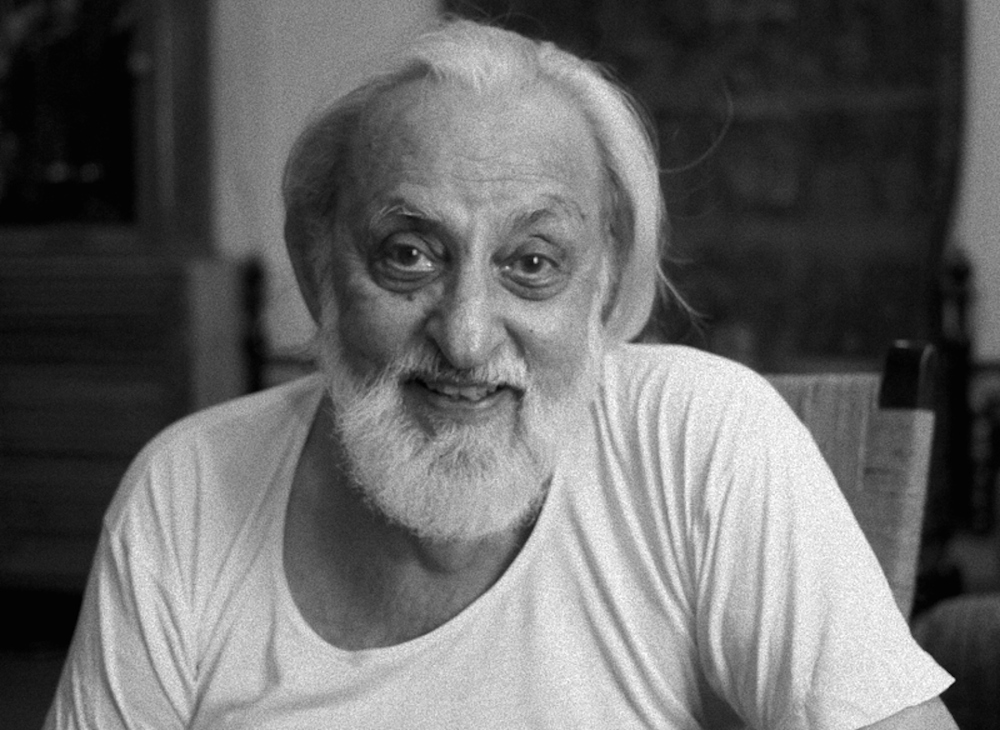

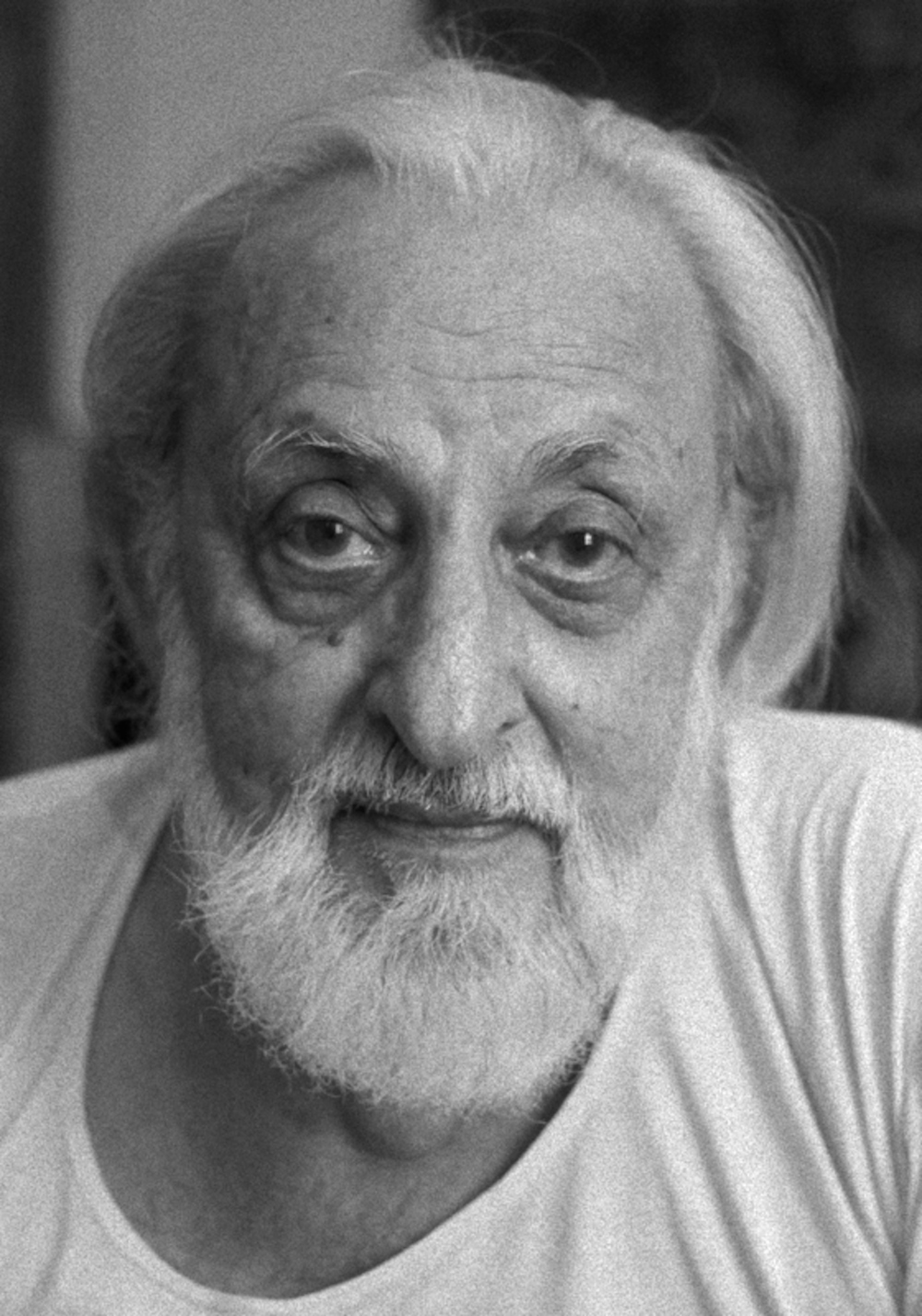

With the whoosh of airplanes periodically taking off in the background, we sat amid distinctive paintings, puppets and patchwork pillows for a noontime conversation with the marvellous director, designer and filmmaker M. S. Sathyu.

Your interest in historical characters for plays – Mughal prince Dara Shikoh, writer Ismat Chughtai, and the poets Sahir Ludhianvi and Amrita Pritam – where did that come from?

It seems to stem from relevance. Dara Shikoh was interesting because the communal forces in India are becoming stronger, and although Dara Shikoh is historically based in Shah Jahan’s time, he’s completely pertinent today. He’s one of the characters in Indian Mughal history who has been neglected; nobody talks about Dara, very few people even know about his work. And Sahir was only one of the characters in my Amrita – there were so many people who came into Amrita Pritam’s life – poets, writers, painters – and Sahir was in love with her. Amrita lived with another painter and illustrator called Imroz for 40 years – and in those days this was pretty revolutionary, not getting married. Her poetry and prose was illustrated by Imroz. All the other characters the play is about are no more, but he is still alive and living in Delhi. Politically, however, Amrita is not my cup of tea – I don’t belong to that kind of thinking at all.

What makes certain characters and situations appealing for you?

I’m a Leftist and subjects that have a lot of social and political relevance are important. I don’t do plays or films without that in my mind. You have to expose, make people think. The solutions are found by the people only; your role isn’t to give them definite answers. Most of the time people aren’t even aware of the problem; they become immune to the whole thing. This is where theatre and cinema come in, to shake them up.

Does politics play a role even when creating stage design?

India simply does not give enough importance to stage, costume, and lighting – the amount of interest people should take… this audience hasn’t been made to care enough. The aesthetics of cinema and theatre are wholly dependent on how ambience and atmosphere are created. You can sometimes make a political statement using your design – I’ve done some plays which are very satirical, like Bakri and Moteram ka Satyagrah. Another play was based on Brechtian play The Resistible Rise of Orturo Ui which was about the rise of Nazism in Germany, and how they could’ve checked it. My adaptation associated the same concept with the Shiv Sena taking over Bombay and even the rest of Maharashtra, and you see how they continue to rule today. In this play, the set has a market and trader’s association, and on the wall is a symbol which is something like a kamal (lotus) which has taken the shape of a worm-eaten cauliflower… Few people understand and many don’t, but that doesn’t matter. Everything in theatre and cinema has a covert reason, but it’s not necessary that everybody be perceptive enough to catch it. This is how you make a statement, I suppose.

You could also take the instance of Safdar Hashmi, a theatrewallah who was murdered a few years ago by Congress goons when he was doing a street play. We did Moteram ka Satyagrah – the last play he wrote before he was killed – and I used his portrait in my stage design. He had been inspired by one of Premchand’s characters, so I had two huge pictures of Safdar and Premchand on the wall. They were black and white line drawings, but I gave Safdar a red scarf. That was enough to say who he was.

Which historical figures’ philosophies do you most resonate with?

I am not necessarily inspired by one character, instead more impacted by their social backdrop. If you take my film Sookha, it is about how the nexus of the police and administration works when trying to achieve political aims – how the problem of hunger, of people looking for food and water, can be manoeuvred by politicians, turning it into a communal riot. This kind of thing happens and I try showing it in detail. The statement you make is important – otherwise why do it?

So you completely do not agree with the “art for art’s sake” school of thought?

There is nothing of meaning in that slogan. Art is for the people – to enlighten them, elevate them. Whether it is a painting or a song it has a definite, definite social purpose, and is not just done… for the fun of it. Such slogans denote that there is some degeneration in the thought processes of the artist.

And you have never given aesthetic choices any reign over the political ones?

No, they go hand in hand. There are so many problems, and we have a medium! The choice to show something of purpose to the people is a mighty responsibility.

If you were to go back in time and converse with three figures from our history, who would you most want to talk to?

You see, there have been so many theatre and film people who have done a tremendous amount of very meaningful work. Somewhere or the other they remain in your subconscious. Take a character like Charlie Chaplin – granted that he was performing slapstick, but the whole time there was a satirical undercurrent to his humour, whether it was Gold Rush or The Great Dictator. You could trace how deep the political thought was.

I haven’t worked with too much history actually, but I’m working on a Hindustani language play on Anarkali at the NCPA currently. It’s spoken in very accessible Urdu, and is about a conflict between a father and son who fall in love with the same woman. While it doesn’t really raise any political questions, I’m trying to recreate an era’s atmosphere; I’ve treated the set and costume inspired by Mughal miniature paintings. You see, visual perspective is a vanishing line, but in Mughal art miniatures, the vanishing line isn’t there! There is perspective to be sure, but it is mounted one above the other. We come to the same plane but there are still different levels, and very few designers have tried to use this element as far as my knowledge goes – some Chinese and Japanese designers have, but no Indians.

From Mysore to Bombay – how did this journey begin for you?

I took an interest in designing and backstage work in the 50s… From then on, I’ve developed a lot of work. Many of my designs since have been lost, but I still have quite a collection to show and talk about. You see, when I came to Bombay from Mysore I didn’t know any of the local languages – no Hindi, Marathi, Gujarati, or Urdu; only my mother tongue Kannada and some English. Not knowing how to verbally express myself in theatre, I decided to take up designing. I had a little bit of interest in painting – used to paint when I was younger – and this helped a fair bit. I mean, I’m not academically trained in any field! All I’ve learned is from watching others.

Which designers did you follow or observe who have stayed with you ever since? Do you believe that formal education received in universities can help develop the kind of creativity you learned by watching first hand?

There were many British designers, German designers, Americans and Russians also, and some Indian film makers and theatre persons who had created very interesting visual ambiences. There have been many who have contributed – directly or indirectly – to my way of thinking.

As for the classroom, you develop a craft, you know. You have to learn a craft, without which you cannot design. It helps to go to school to paint and sketch… it helps, but it is not enough. Your contribution comes into it, your way of thinking. Both social and political attitudes are very important. One uses light on stage first to illuminate, and secondly to create an ambience – and this is what a good lighting designer must do. There is a difference between the two – how you use angles, distance – it all assumes importance.

Watching a Van Gogh documentary the other day, what struck us was the realisation that Van Gogh moved from the city of Paris to the countryside of Arles because he was looking for brighter colours, bigger landscapes in his works. Have you ever travelled in this way for your craft?

I have travelled to many a historical place – to temples, mosques, cathedrals – and have seen every kind of landscape. It’s not like you sit in a room and you become… you know. Many years ago when I was designing the Shakespearean play Othello, I was drawn by contrasting black and white mediums, which would bring out the contrasts in the lovers’ characters – Othello was a Moorish man, and Desdemona was fragile and delicate… The director wanted to place the play in Kashmir in the time of snow. I designed it, and you could really see the snow!

There are people who use various aspects of nature very interestingly. With a director like David Lean, you got Lawrence of Arabia; the whole film was based in a desert, and how this man used the storm, the dust, people looking for water! The same director in Zhivago used a backdrop of snow; in another film he used the sea with all its peacefulness, all its destruction. This is how some directors look towards nature to tell a story.

When Girish Karnad wrote Tughlaq in Kannada, I designed its very first production in Delhi. For background research, I took the entire cast along with their spouses and children to Tughlaqabad. We saw the huge fort, totally ruined. We had picnics, but it was really a study. We all had to see for ourselves how Tughlaq was ahead of his times. When the next day we started rehearsing, we all had the history. The subject defines what the process will be.

Before shooting Garam Hawa, I went to Agra, a place I had never seen before, this historic city with its narrow lanes and bazaars. When I was doing a film in Calcutta, it involved staying there and working with the students involved in the early Naxal movements. One cannot shoot at random, one has to prepare oneself. I suppose everything is like that – you must do a lot of homework!

Have you ever been intrigued by productions not situated in the real world as we know it, sans historical and political backdrops?

There’s always science fiction and fantasy, and the question of whether something exists or doesn’t. The idea of paradise, for instance, is very dramatic. There’s a very interesting film called A Matter of Life and Death by Emeric Pressburger and Michael Powell, two British directors. Joining them for this movie and many others (like The Red Shoes) was a German art designer called Hein Heckroth. This trio is one that has absolutely inspired me.

In this particular movie, there is a British test pilot in love with an American girl from the army… or something like that. He is involved in a plane crash, and is wounded, but not dead. He’s taken to the operation theatre with all its lights, and he’s fighting for his life. Then, a messenger from… wherever he comes from, wants him; it is time for him to go. And here is your conflict. The directors create a whole stadium-like space to depict heaven, and all the great thinkers of the world who are dead and gone are all there. Aristotle. Voltaire. Gandhi. Soldiers who have died at war. There, the argument about his time truly being up takes place. Ultimately, they take him back to earth using… a staircase vanishing into the sky. Actually, it was an escalator. To have used one in those days, in the 40s, as a set piece! People from heaven accompany the pilot to Earth to find the girl. They find her and ask her, “Ultimately, would you sacrifice your life for him?” She says, “Yes, I wouldn’t mind.” And a decision is made. Note how this set design created a heaven that was, for all practical purposes, a courtroom! I saw it when I was in high school. We used to get morning shows of these English films, and we’d cut school and go watch them – I used to watch a film every day if I could manage it!

You have also worked with ballet and other dance forms?

I have. I was very fond of ballet; it’s one of my weaknesses, and one of my strong points too! I really enjoy the choreography. I have adapted a play called Smashana Kurukshetra, about the eighteen day war of Mahabharata between the Kauravas and the Pandavas. After eighteen days on the battlefield and the countless dead and injured, everyone is looking for their kith and kin. There onstage, I recreated the battle scenes using kalaripayattu, which is Kerala’s martial art, to create an ambience of war. An old woman comes on stage later, wanting to know why her grandson fought this fight, which was just an internal dispute within a family. This was her question, and she wanted to find his body. Similarly, Kunti is searching for Karna. The Pandavas interrogated her, “You’re looking for our enemy’s body? Why?” Only then did Kunti reveal that Karna was her eldest, her son out of wedlock when she was in love with the Sun God. I used many ballet movements to depict this vignette. Karna is never shown, but a shroud of white cloth is held in four corners by dancers. They use their synchronised movements, lower the shroud onto the floor. Suddenly, you see. This is Karna.

This was an anti-war play talking of the futility of battle, originally written in Kannada by K. V. Puttappa. He brought it up to the partition in 1947. I brought it further to Kargil, and called it Kurukshetra se Kargil Tak. I worked with ballet troupes from Bombay as well as Bangalore because, you see, in theatre you can use everything! Acrobatics, martial arts, dance. Anything goes. The choreographer I worked with in Kurukshetra has been working for the past few months on a film with the dance traditions of the Devdasis, where she shows temples in the background and highly modern choreography to go with them. So you see, nothing is restricted.

Are there particular themes or eras you most want to work with?

One lifetime isn’t enough to work with all of one’s favourite subjects, there are so many! Basically, whatever one does, one must be thorough; there is no middle ground to be found here. You cannot shun hard work. I have with me a film script where I use the Indian Space Research Organisation, and bring out the social dilemmas emerging in the background. A highly qualified scientist coming from an orthodox Brahmin family happens to come across a jailbird, an auto driver, a Dalit. He is an uneducated dropout, and she has a PhD in aerodynamics. Set in ISRO and based it on a real story, I’ve used scientists and satellites, looked at how rockets are made in Kerala, satellites are produced in Bangalore and the launching takes place in Shriharikota in Andhra Pradesh! The scene is set, and so is my dilemma – even though these people are ready to send people to the moon, they are bogged down by innumerable social and religious dogmas. All their education and all their modernity comes to naught.

Do you see? You have to learn from so many sources, and read and read. You have to read a lot of literature, history, science. It helps when you understand for yourself.

Design… it’s not just drawing.

Interviewed and photographed by Tanvi Shah.

To experience first hand the stories of Mr. Sathyu, and to hear him talk about “Designing for the Theatre: A Journey”, join us at 5 pm on July 4, 2015 at MCubed Library in Bandra. This session is part of Junoon’s Mumbai Local series.

Reblogged this on power doom.